When art historian Kaja McGowan was on a Fulbright Fellowship in Indonesia in 1990-91, researching rituals of life process with a high priestess in Bali, one particular practice caught her attention.

“Balinese families frequently visited the priestess’s home with offerings, borrowing a single stuffed bird of paradise for their loved ones who had passed away,” said McGowan, associate professor of history of art and visual studies in the College of Arts and Sciences. She learned that Balinese Hindus use one ceremonial bird again and again, thus both practicing their religious beliefs and sustaining populations of the protected bird-of-paradise species native to Indonesia.

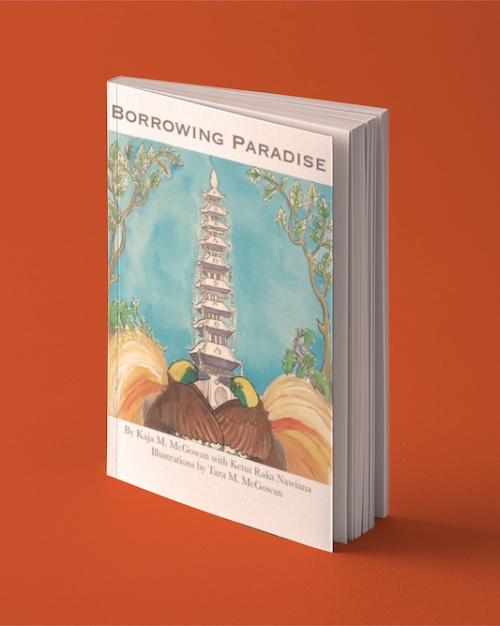

In “Borrowing Paradise,” her new book for children, McGowan brings this community-centered ritual to life with a story inspired by a family she met during her Fulbright. The book is illustrated with watercolors by her sister Tara McGowan.

Her story follows Surya, a Balinese boy who plays a key role in the elaborate Hindu ritual set in motion when his beloved grandfather dies. A sarcophagus shaped like an elephant-fish is built, a tower is constructed, and a procession of family and friends carry both to the oceanside for cremation. The boy helps prepare the towers and carries the stuffed bird-of-paradise during the ritual procession to guide his grandfather’s soul to heaven so it can be reborn.

“It’s a story of a community working together to perform rituals that help them come to terms with grief while also achieving greater environmental sustainability,” McGowan said.

The College of Arts and Sciences spoke with McGowan about the book.

Question: What Balinese religious practices include the protected bird-of-paradise?

Answer: In Balinese Hinduism, the body is believed to be nothing more than a temporary shell, a container for the soul and its anchor to earth. All thoughts at the time of death are concentrated upon the soul and its passage to heaven. Hastening the soul on its way is of utmost importance.

It is often assumed that ecological awareness is a new phenomenon, but the Balinese custom of “borrowing” a stuffed greater-bird-of paradise (Paradisaea Apoda) from the royal palace or a high priest’s house for cremation ceremonies to serve as a key ritual accelerant for the soul’s journey has a long history. Exactly when this exchange with the Aru Islands began is still a mystery, but presumably it has been going on for centuries.

Today, members of the birds-of-paradise species enjoy legal protection, and hunting is only permitted at sustainable levels for the ceremonial needs of the indigenous population. I encourage everyone to check out the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Birds-of-Paradise Project.

Q: How does the story of Balinese Hindu practice and the bird-of-paradise provide an example for environmental action?

A: Borrowing something implies that you will return it, and it is this concept of “return” that most intrigues me. “Re-using” one stuffed bird of paradise to assist the souls of an entire village over time argues for a more ecologically sustainable approach to preserving nature.

Q: How does this children’s book relate to your academic research?

A: My research addresses the slow arc of an academic turn from objects to materials with an increasing emphasis on living, vibrant and dynamic processes – of (re)making, (re) building, (re)using, (re)conceiving. The island of Bali in Indonesia is at the heart of these excursions.

With its focus on the dynamic role of Bali’s active volcanic landscape, my research contributes to the emerging field of eco-art history — examining performance, literature, ritual offerings, architecture, sculpture, painting, jewelry, textiles, and photography at the oft-times turbulent intersection of the natural ecosystem and embodied cultural production. Birds-of-paradise, woven threads, metal wire, salt reed grass, coins, hair and jewel-like substances are just some of the lively protagonists that emerge.

Q: Would you tell us about the book’s illustrations?

A: The illustrations for “Borrowing Paradise” are an extended family affair. The illustrator, Tara McGowan, is my sister, an artist and storyteller who researches, illustrates and performs kamishibai (Japanese paper theater). Our father, Dorian McGowan, was an art professor for more than 50 years at Lyndon State College (now Vermont State University) and his watercolors of Bali done during a sabbatical year serve as inspiration for some of the watercolors.

Others were painted in close conversation with my partner, Ketut Raka Nawiana, and our son, Surya, who served as the model for the book’s main protagonist.