A faculty committee is exploring Cornell’s history as a land-grant institution and the nation’s dispossession of Indigenous peoples.

Through the “Cornell University and Indigenous Dispossession Project,” the faculty committee formed by the American Indian and Indigenous Studies Program (AIISP) in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) is investigating Cornell’s legacy as the institution that profited more than any other from the Morrill Act of 1862, which enabled the establishment of 52 land-grant universities.

The act transferred to universities providing instruction in agriculture and “mechanic arts” federal land that had been taken previously from Native Americans – often violently or through forced treaties – and whose subsequent sales seeded endowments.

“Cornell and every land-grant institution in the United States need to face up to this morally,” said Kurt Jordan ’88, associate professor of anthropology in the College of Arts and Sciences (A&S) and director of AIISP. “This is an important follow-up to the university’s initiatives promoting equity and justice, to recognize that Cornell has benefitted from settler colonialism in a very tangible way.”

In addition to Jordan, the faculty committee includes Eric Cheyfitz, the Ernest I. White Professor of American Studies and Humane Letters (A&S); Jeffrey Palmer (Kiowa), assistant professor of performing and media arts (A&S); Jon Parmenter, associate professor of history (A&S); Jolene Rickard (Tuscarora), associate professor of the history of art and visual studies (A&S); Troy Richardson (Saponi/Tuscarora), associate professor in AIISP (CALS); Jane Mt. Pleasant ’80 (Tuscarora), director emerita of AIISP (CALS); Urszula Piasta-Mansfield, associate director of AIISP (CALS); and Meredith Palmer (Tuscarora), a Presidential Postdoctoral Fellow in science and technology studies (A&S).

“Our task is to present information and opinion about the implications of Indigenous dispossession for Cornell and its responsibility to address that history,” Jordan wrote in the opening entry of the blog that the project is using to share research and perspectives from contributors.

On Oct. 12 – Indigenous Peoples Day – AIISP will host a 7 p.m. panel discussion about the project, preceded by a 4:30 p.m. webinar about Indigenous student activism at Cornell since the 1960s.

Members of the AIISP committee and university leaders met in late August and discussed their shared interest in learning more about this aspect of Cornell’s history. Topics included administration support for the faculty’s research on the land grants, the committee’s planned consultations with affected Indigenous communities and faculty-identified needs for university support for Indigenous scholarship, faculty and students.

In a Sept. 4 statement updating the university’s racial justice initiatives, President Martha E. Pollack and Avery August, Ph.D. ’94, vice provost for academic affairs and chair of the Presidential Advisors on Diversity and Equity, called the meeting important and productive.

The leaders said they were committed to working with the faculty to advance initiatives including “a public institutional statement acknowledging our land-grant history, engagement with the Indigenous peoples impacted by our land grant and by Cornell’s New York campuses, and a more overt and robust inclusion of the perspectives of Native American peoples in our ongoing work,” according to the statement.

The faculty’s call to action was spurred in part by a March article in High Country News that traced the Morrill Act’s transfer of more than 10.7 million acres of land that had been occupied by nearly 250 Native American tribes.

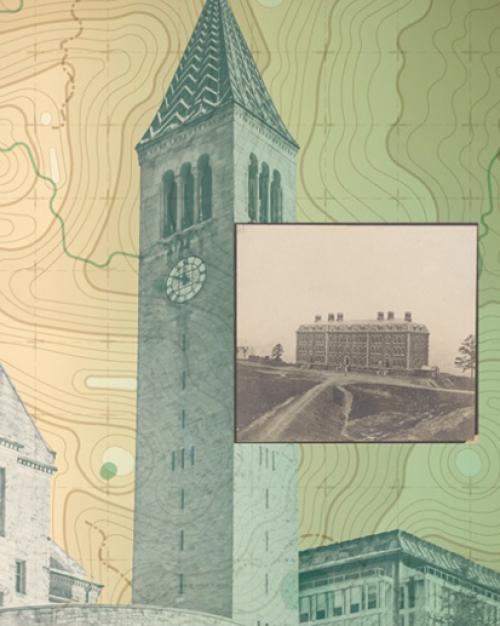

As the nation’s most populous state when President Abraham Lincoln signed the act, New York was allotted “scrip,” or vouchers, for nearly 1 million acres that ultimately spanned 15 states (the parcels are mapped in the blog). By the time the last parcels were sold in 1935, the land had generated more than $5 million for Cornell’s endowment, far more than any other land-grant institution.

Previous research has documented university founder Ezra Cornell’s personal investment of $500,000 to buy scrip, and his selection and management (including logging) of valuable Wisconsin timberlands – activity unique among land-grant recipients – but the reported scope of Cornell’s impact surprised many faculty members.

In a new research paper posted on the blog, Parmenter wrote that “Cornell University’s particular place in Morrill Act-related Indigenous dispossession may be considered exceptional.”

But whereas High Country News linked Cornell to as many as 63 treaties or seizures, Parmenter concluded that seven particular treaty surrenders of Indigenous land or resources in Wisconsin, Minnesota and Kansas later generated direct benefits to the university. Beyond those states, he said, it was difficult to directly associate the university with specific dispossessions because Ezra Cornell sold his unallocated land vouchers and had no say in the parcels ultimately selected.

“There is an opportunity to extend our appreciation of those who came before us,” Parmenter said, “beginning with those Indigenous nations whose political and economic circumstances changed forever after the seven American treaties that converted much or all of their homelands into ‘public lands.’”

The faculty committee plans to consult with Native American nations that ceded land sold through the Morrill Act, as well as with the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫʼ (Cayuga), on whose land Cornell’s Ithaca campus sits, and others across New York state where Cornell has a presence.

Rickard said that just as many institutions are publicly reckoning with legacies linked to enslaved labor, Cornell must understand and acknowledge how central Indigenous dispossession has been to its founding and ongoing operation.

“The legacy of dispossession is not an easy thing to embrace for anyone,” Rickard said. “I think if we face this, we can be a model of how to be an educator for a just society. If we don’t face it, it will always be a thorn.”