Original article

It remains as shocking today as it was when it was first printed in the late eighteenth century: an intricately detailed drawing of hundreds of human bodies, lying in the cargo hold of a slave ship en route from West Africa to the Americas. The accompanying text is no less disturbing. It details, among other horrors, how each male captive was jammed into a space just six feet long by sixteen inches wide; if a ship was even more tightly packed, men could have as little as nine inches of width, lying on their sides or atop each other. “The slaves are never allowed the least bedding, either sick or well, but are stowed on the bare boards, from the friction of which, occasioned by the motion of the ship, and their chains, they are frequently much bruised,” the author lamented, “and in some cases the flesh is rubbed off their shoulders, elbows, and hips.”

Finley (seen in her Goldwin Smith office) spent two decades researching what would become the topic of her book.Lisa Banlaki Frank

Entitled Description of a Slave Ship, the 1789 print is one of several such images produced by British activists campaigning to outlaw the slave trade. As Cornell art historian Cheryl Finley points out, while the trade yielded immense profits and founded many personal fortunes, the British populace was largely insulated from it, as the Middle Passage—the leg of the triangular trade route in which ships carried their human cargo—didn’t touch their shores. “The image exposed for the very first time, in a calculated way, the system of the transatlantic slave trade,” says Finley, speaking with CAM in her book-lined office in Goldwin Smith, where a framed copy of Description of a Slave Ship hangs above her desk. “By actually putting figures representing the enslaved people in the ship plan, it was able to, in a sense, peel off the top, look inside, and give a three-dimensional view. It illustrated very clearly what the human toll was.”

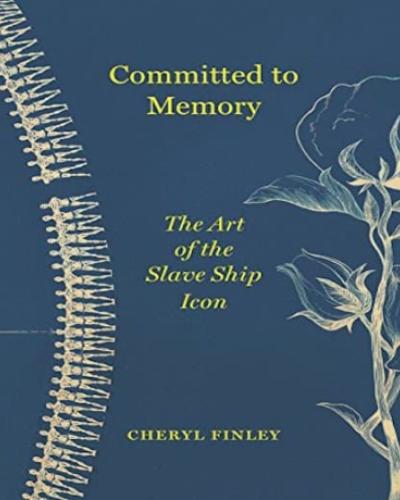

Finley has been studying Description of a Slave Ship for some twenty years—not just the image itself, but the many ways in which it has been repurposed and reinterpreted, particularly in the past half-century. Last summer, Princeton University Press published her book Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon, a richly illustrated hardcover in which Finley parses the legacy of the eighteenth-century prints, which helped fuel abolitionist movements in Europe, the U.S., and beyond. “By the end of the eighteenth century, more than 200,000 had been circulated around the Atlantic rim,” Finley says. “As a piece of paper, something very ephemeral, it really got around.”

Committed to Memory: The Art of the Slave Ship Icon Price: $46.58Was: $49.50Finley first encountered Description of a Slave Ship during her graduate work in art history and African American studies at Yale in the late Nineties, when she took a course on eighteenth-century material culture at the school’s Center for British Art. While some of her fellow students were doing projects on fine china and silver tea sets, she recalls, she found herself fascinated with “the source of wealth that created this culture of consumption”—so she did a presentation on how the slave trade shaped and enriched the port city of Liverpool, a nexus for British-funded slaving voyages.

She came across the print during her research; as she notes, around that time “a lot of things were going on that made this image come out of the archives,” including the debate over whether the U.S. government should pay reparations to African Americans for their ancestors’ enslavement. In 1998, for example, the New York Times illustrated an essay pondering America’s culpability in the slave trade with a version of Description of a Slave Ship. (Finley reprints the story in her book.) Another work on her office wall, which she acquired at a conference that same year, depicts the iconic ship beneath a diagram of a Baltimore jail—underscoring the connection between slavery and the modern prison industrial complex, in which black men are incarcerated in disproportionate numbers. Says Finley: “It was a moment in time when this image was being used to illustrate, on the one hand, a history that was hundreds of years old—but it also suggested a situation that had not really changed.”

In Committed to Memory, Finley explores how the slave ship image has been incorporated into modern artworks around the globe and in a wide variety of media. There’s La Bouche du Roi (The Mouth of the King), a room-sized multi-media work by an artist from the West African nation of Benin that was acquired by the British Museum; it includes oil drums and other materials laid out in the configuration of the slave ship’s captives. In a Baptist church in Chicago, the ship forms the torso of a shackled, Christ-like figure in a stained-glass window. The cover of Finley’s book, an acrylic painting by Malcolm Bailey from 1969 that she calls “horrifically beautiful,” comprises skeletal sketches of men linked together in a configuration reminiscent of the slave ship, alongside a delicate botanical drawing of a flower. As she notes in Committed to Memory, the ship diagram even appears in a book from the American Girl doll franchise—a biography of Felicity, a character who lives in the South during the Revolutionary War era.

The slave ship diagram as reimagined in a Chicago church window.Provided

Finley, who began her career in the curatorial world, vividly recalls the moment when she decided to shift to academia. She was in the audience during a sale at a prominent Manhattan auction house; the item up for bid was Man in a Polyester Suit, a controversial photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe depicting the torso of a black man with his penis exposed. Finley was one of just three African Americans in the room; another was the porter displaying the photo. She already found the artwork distasteful, an example of “negrophilia.” So she was horrified when the porter held up the photo—which lined up against his body perfectly, as though he were the man depicted in it—and the audience erupted in laughter. “I was crumbling in my seat,” she recalls. “I felt for him. I was embarrassed for him, although he probably was completely unaware. I realized that I wanted to be in a room where there are more people who look like me, and like him.” With the aim both of working in a more racially inclusive environment and of training a more diverse generation of curators and art historians, she says, “that fall, I applied to grad school.”

A professor on the Hill since 2004, Finley will be teaching some of the themes in her book this spring in an undergrad lecture course on slavery and visual culture. Last semester, she taught a class on Blaxploitation cinema—her office décor also includes a giant poster for Friday Foster, a 1975 thriller starring Pam Grier—as well as a course on graduate research methods in art history. It was during a meeting of the latter that, for the first time in her two decades of studying the slave ship print, Finley got a visceral sense of how widely it had spread in its day. She had taken her students to Cornell’s Rare and Manuscript Collections in Kroch Library, which has numerous versions of the iconic image in abolitionist tracts and broadsides. “As a researcher, I’d never had the opportunity to sit down and be surrounded by them,” she recalls. “It was mind-blowing.”